Public debt has doubled in Africa since 2010, reaching 65% of GDP in 2022 compared to 32.7% in 2010. The continent has also witnessed a diverse creditor portfolio, with Paris club members and non-members (notably China) making up 37% and 17% of the total external debt respectively by 2022. Since 2007, $140 billion worth of Eurobonds have been issued by African sovereigns (representing 30% of the region’s external debt) except for South Africa and Seychelles.

According to the World Bank’s new International Debt Report, the poorest countries (the majority of which are in Africa) eligible to borrow from the International Development Association (IDA) spent $46.2 billion on long-term public and publicly guaranteed debt repayment in 2021. This amount is equivalent to 10.3% of the countries’ exports of goods and services and 1.8% of their Gross National Income (GNI), a significant increase from 2010 when the percentages stood at 3.2% and 0.7% respectively.

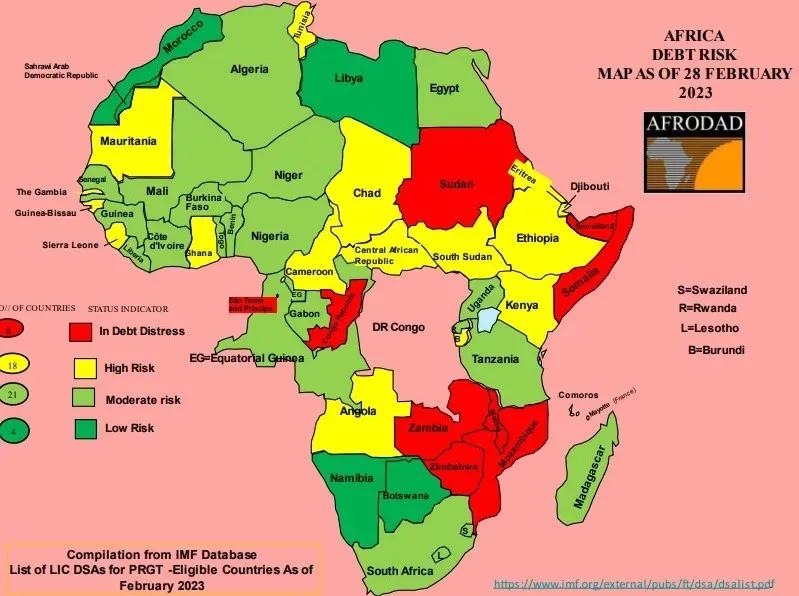

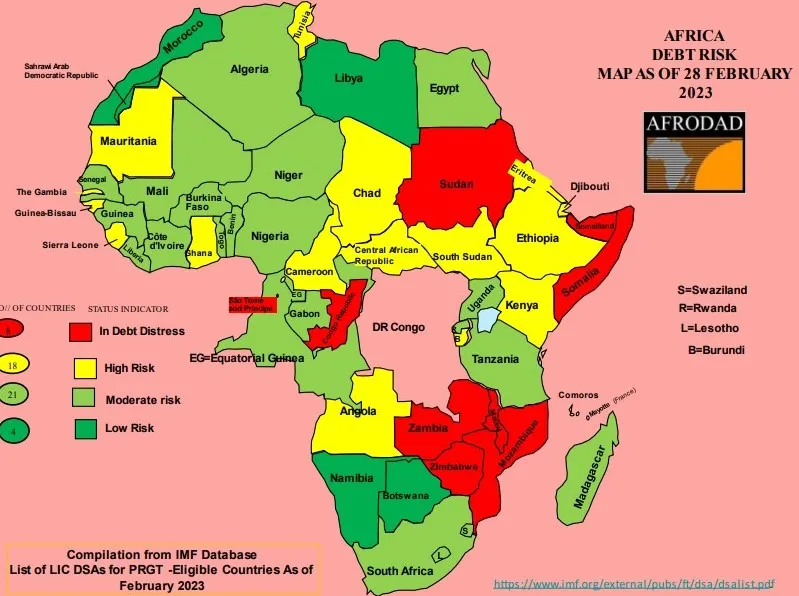

The runaway debt burden in Africa has led to many countries defaulting or at the brink of defaulting on their external debt in a desperate move to restore macroeconomic sustainability. 23 low-income African countries are at high risk, or already in debt distress according to the IMF and World Bank. 4 African sovereigns namely Zambia, Mali, Ghana, and Mozambique have defaulted or stopped debt servicing and are turning to the IMF for support.

Figure 1: Africa Debt Risk Map, Feb 2023

In 2020, Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The country is struggling with high levels of debt, which had been fueled in part by borrowing to fund infrastructure projects. In November 2020, Zambia reached a deal with the IMF for a $1.3 billion loan to help address its debt challenges.

In early 2022, Mali became the second African nation to stop external debt servicing due to regional sanctions over a coup. However, following the lifting of the sanctions in July last year, Mali has honored all missed payments.

Ghana is the third African state to default on external debts. In December 2022, Ghana facing its worst economic crisis in a generation suspended payments on most of its external debt, calling it an “interi e ergency easure”. In 2015, the country signed an IMF progra to help address its debt challenges, which included measures to improve revenue collection and reduce spending.

Mozambique has been struggling with a debt crisis since 2016 when it emerged that the country had taken on large amounts of secret debt. The revelations led to a suspension of aid from international donors and a default on some of its debt. In 2019, Mozambique reached a restructuring deal with its creditors, which included a reduction in the value of its debt.

Kenya is also reeling under a huge public debt burden and has experienced a credit rating downgrade three times in six months. In the latest rating in May 2023, Moody’s downgraded Kenya’s creditworthiness from B2 to B3 citing increased liquidity risks faced by the government. The country is currently under a 38-month program by the IMF. Recently in May upon completion of the fifth review of the IMF program, Kenya was granted access to $544.3 million with the country expected to adopt agreed policy reforms.

While it is true that many African countries have high levels of debt, it is important to recognize that the root causes of this problem are complex and multifaceted. The current international financial architecture has contributed to the debt problem in Africa. The contemporary financial ecosystem is often driven by a neoliberal, private, and profit-focused approach to development. This approach emphasizes the importance of attracting foreign investment and promoting exports, often at the expense of domestic industries and social welfare programs. An example is the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that were promoted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in the 1980s and 1990s. These programs required African countries to implement a range of economic reforms, including privatization of state-owned enterprises, liberalization of trade and investment, and reduction of government spending on social programs. While these reforms were intended to promote economic growth and reduce poverty, they often had the opposite effect, leading to job losses, increased inequality, and rising debt levels.

Another criticism of the international financial architecture is that it often prioritizes the interests of creditors over the needs of borrowers. For example, many African countries have been forced to take on large amounts of debt to finance infrastructure projects or other development initiatives. However, when these countries are unable to repay their debts, they are often subjected to harsh austerity measures and other punitive measures by their creditors. This has led to a vicious cycle of debt, as countries are forced to take on more debt to repay existing debts.

Debt has been growing faster than revenue in many African countries, contributing to a range of economic challenges on the continent. In addition, there are certain challenges related to the global trading system that has limited Africa’s ability to move up in the value and supply chains in the way that some other regions have.

One of the key factors contributing to Africa’s debt problem is a lack of economic diversification. Many African countries are heavily reliant on commodity exports, which can be volatile and subject to price fluctuations in global markets. This can make it difficult for countries to generate sustainable revenue streams, hence contributing to the rising debt levels.

In addition, the global trading system is often stacked against developing countries, including many in Africa. This has made it difficult for these countries to compete on a level playing field and to move up in the value and supply chains like other countries in the Global North. For example, developed countries often impose high tariffs on imports from developing countries, which can limit their ability to access key markets. Lastly, there are certain challenges related to industrialization on the continent. Many African countries have struggled to build strong manufacturing sectors and rise in global production. This is due to a range of factors, including limited access to finance, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of skilled labor.

Further, the debt problem has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, the climate emergency, and the rising global interest rates. The pandemic has had a devastating impact on many African economies, which were already struggling with high debt levels and limited fiscal space. To respond to the pandemic, many African countries have had to increase borrowing and take on more debt, to fund healthcare systems, social safety nets, and other critical programs. In addition, the pandemic has led to a decline in global demand for African exports, which has further limited revenue streams and contributed to rising debt levels.

To address these challenges, the international community and development partners introduced some interventions which have been limited in scope and have not gone far enough to address the root causes of the debt problem in the region.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) was launched in 2020 to provide temporary relief to developing countries that are facing debt distress as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the initiative has provided some relief to African countries, it has failed to compel all creditors to participate. Only 45 beneficiary countries of the 73 eligible low-income economies have sought to suspend debt payments to official bilateral creditors. Since only a limited scope of debt service is covered, deferred debt service through July 2021 totaled only US$4.6 billion.

The G20 Common Framework for debt treatment was launched in 2021 to provide a more comprehensive approach to debt relief and restructuring for developing countries beyond the DSSI. Only Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia have applied for the framework and restructuring measures have not gone nearly far enough. The framework has become ineffective in addressing debt challenges due to the absence of clear procedures and timelines for debtors and creditors, a lack of clarity on how different creditors will be treated, and a geopolitical rift, including the conflict between Tigray forces and the government in Ethiopia. LICs that apply for the framework are likely to be downgraded, as Ethiopia recently experienced.

Similarly, the allocation of Special Drawing Rights by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been seen as a potentially important tool for providing additional liquidity to developing countries, including those in Africa. However, the amount of SDRs that have been allocated so far is insufficient to fully address the debt problem in the region. In the latest allocation, Industrialized and Emerging Economies received SDR 418.4 billion (65%) while Low-Income Countries/ Developing Economies received a paltry SDR 231.6 billion (35%). The current quota system avails resources disproportionately in favor of developed countries which in many cases do not need the allocation since they have broader access to monetary instruments and reserve cash.

Addressing the debt problem in Africa and the associated economic challenges requires a multi-faceted approach that involves action at the national, regional, and global levels. One of the key factors contributing to unsustainable debt levels in Africa is the lack of transparency in debt management. Countries need to be more transparent about their debt and borrowing practices, including debt contracts, terms, and conditions. This will help to prevent irresponsible lending and borrowing, and promote responsible debt management.

Strong institutions at the national, regional, and international levels are essential for effective debt management. At the national level, countries need to strengthen their debt management offices and regulatory frameworks to ensure that borrowing is done responsibly and that debt is managed effectively as espoused in the African Borrowing Charter. At the regional and international levels, institutions such as the African Development Bank and the International Monetary Fund need to work together to provide technical assistance and support to countries in managing their debt, including building institutional capacity for debt management, and providing training and capacity building for debt management officials.

The public has a right to know about the borrowing and debt management practices of their governments. Governments need to involve the public in the decision-making process on borrowing and debt management and ensure that citizens are aware of the risks and benefits of borrowing as enshrined in the Harare Declaration.

Finally, there is an urgent need to reform the current international financial architecture to help solve the debt problem. It is essential to have in place a new global financial ecosystem that adopts a comprehensive debt sustainability framework and credit-rating assessment, bringing together all creditors, both official and private in sovereign debt restructuring. In essence, the new framework should be designed to promote responsible borrowing and lending practices, prevent over-indebtedness, and ensure that debt is managed sustainably. Also, systematic issues like commodity price volatility, trade imbalances, and unfair tax practices that contribute to high indebtedness in Africa should be resolved amicably. All these require intense lobbying by Civil Society Organizations, government officials, and the African Union-a move that would make Africa a Rule Maker and not a Rule Taker.

By Eddy Otieno

Former Intern at AFRODAD